Mummy entered the room with the tea and extended the tray before Paaji. From where she was sitting, Niyati could only see Paaji’s back. He took the steaming cup in his hands and glanced at Mummy once, but didn’t say a word.

Niyati sat trying to complete the picture in the jigsaw puzzle, comfortable sounds of familiarity edging her concentration – the cooker whistling away in the kitchen, the water running from the tap in Paaji’s bathroom as he washed his hands and feet after finishing his tea, the rustle of the newspaper being read by Didi in the living hall.

Mummy came out of the kitchen to open Paaji’s almirah and put out a fresh kurta and his favourite mustard-and-blue checked lungi on the bed, and went back to the kitchen again.

Five minutes before eight, Mummy called out. ‘Nisha, Niyati, come help me in serving Paaji.’

Niyati deserted her game, and Nisha the newspaper. Soon Paaji sat at the dining table. Nisha served the chicken in a large bowl and placed some salad in one corner of his plate. Mummy brought hot, fresh chapatis one by one. Niyati sat on the chair next to him.

‘ What did you learn at school today, beta?’ he enquired gently. As he spoke, he made a small measured morsel dipped in chicken gravy and held it over his plate, waiting for an answer. ‘Lesson two in English and number multiplication up to one hundred in Maths.’

Paaji fed her the morsel he held and nodded approvingly.

‘You should take up music, too, with me sometime, bachche. You can sing well. But you know me, Gudiya, I’m not the kind to force anyone, not even my children.’

‘Yes, Paaji,’ Niyati answered in a sing-song voice.

Paaji always fed her some bites from his plate as he ate dinner, and that made Niyati feel very important and happy.

Niyati smiled back and then stared from the corner of her eye at Paaji as he slowly chewed his food, gracefully relishing each bite, with his mouth completely closed just as he had always taught her to do. She tried to do it just the way he was doing, and then waited for the next morsel from him. But today, Paaji seemed to have momentarily forgotten about her, so she picked a slice of cucumber from the plate to draw his attention to herself. It didn’t help, so Niyati, though confused, stared at him unabashedly.

Paaji was more handsome and kinder-looking than Chandan and Pinky’s father, she thought. Yet, she herself wondered why she was still scared of him. He was not balding like Prakash uncle; in fact his foppish hairstyle and hair that had not greyed at all, unlike Mummy’s, made him look almost boyish. If only Paaji would wear the kind of smart shirts and trousers that Prakash uncle usually wore, but which were so wasted on him. But Paaji only wore kurta-pyjamas, or worse still, the occasional kurta-dhoti!

Niyati had once asked him about this sartorial preference. He had smiled benignly and explained that he was a respected artiste and an example-setting guru to his devoted shishyas whom he taught at the prestigious Sangeet Kala Bharati. He did not go to an office like ordinary men who wore shirts and trousers.

Paaji had then asked Niyati whether she didn’t feel proud when she saw him up on stage in concerts, unlike any of the other fathers she knew.

Nowadays, since Mummy did not have much time, and Didi would refuse outrightly to attend them, Niyati too had stopped going for Paaji’s recitals. But she did remember the ones that she had earlier attended. Didi would jokingly say that these classical music soirees were not meant for people like her who wore jeans. They were for the ‘swish set’. According to her, all the people who attended these concerts could be identified by the swish and rustle of their silk sarees and expensive shawls, as they walked about elegantly, talking in reverential whispers.

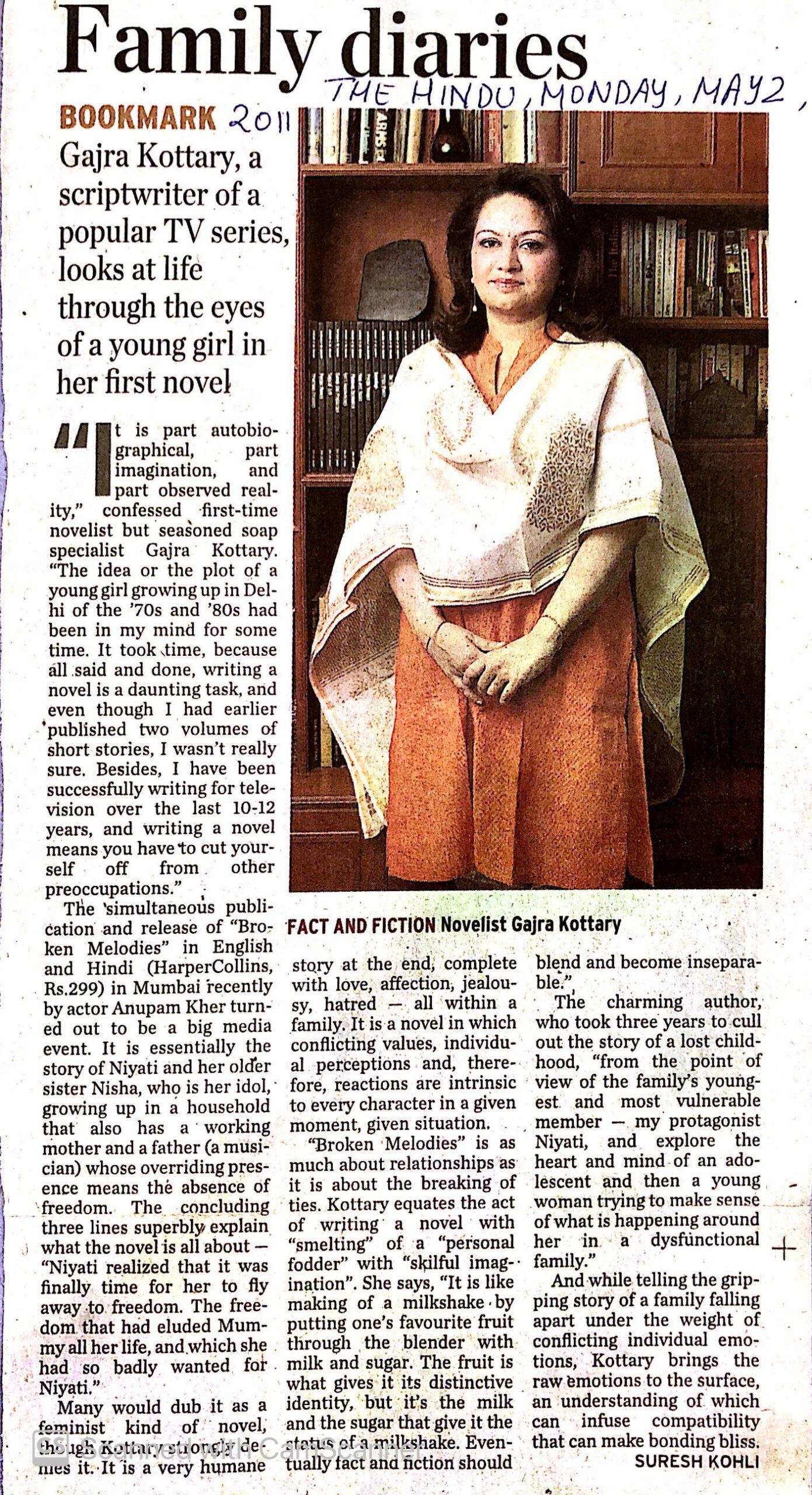

It would always happen in exactly the same way. Paaji would be sitting in the middle of the stage, two of his favourite female disciples on either side behind him accompanying him on the tanpuras. He often took infinitely long to tune the tanpuras onstage, for they had to sound just perfect to his musician’s ear. All through this time, his privileged disciples would lean towards him, looking guilty and deferential by turns. Once they were handed the tanpuras back, the students would be visibly relieved and then settle down to their jobs of accompaniment. And more importantly, of subtly lauding their guru at every twist and turn in his traversal of whichever raga he was singing that day.

As Paaji would begin singing the bada khayaal slowly and majestically, he would sometimes look like a yogi in meditation. Then intermittently, he would run his gaze as discreetly as possible across the rows of chairs in front of him to assess how well attended his performance was. Niyati would meet his eye, as she sat in the front row, her bare legs cold from the air conditioning and feet not reaching the floor.

It was always the first seven or eight rows that would be full of familiar people, and then there would be a random scattering of people in the rest of the auditorium. Paaji would often look momentarily disappointed and then, with a well-hidden sigh, go back to his rendition, espousing philosophies akin to the futility of success and failure in life in this illusory world.

The familiar people in the front row would encouragingly nod their heads to the tabla beats or make hand gestures of appreciation in the air. Paaji’s mood would gradually lift and he would then proceed to sing with complete abandon. In the end, he would always oblige the audience requests to sing his trademark Sufi kalaam, ‘Avval allah noor upaya, kudrat ke sab bande’.

Yes, of course, Niyati felt proud when she saw him up there and noticed the collective appreciative nodding of heads of people in the audience as he sang. Yet, she wished he would wear a shirt and trousers once in a while like normal fathers. But he just never did. That’s why Niyati did not like him coming to her school on parent–teacher meeting days, and so it was always Mummy who attended them. Luckily for her, Paaji had never offered, let alone insisted, on going there.

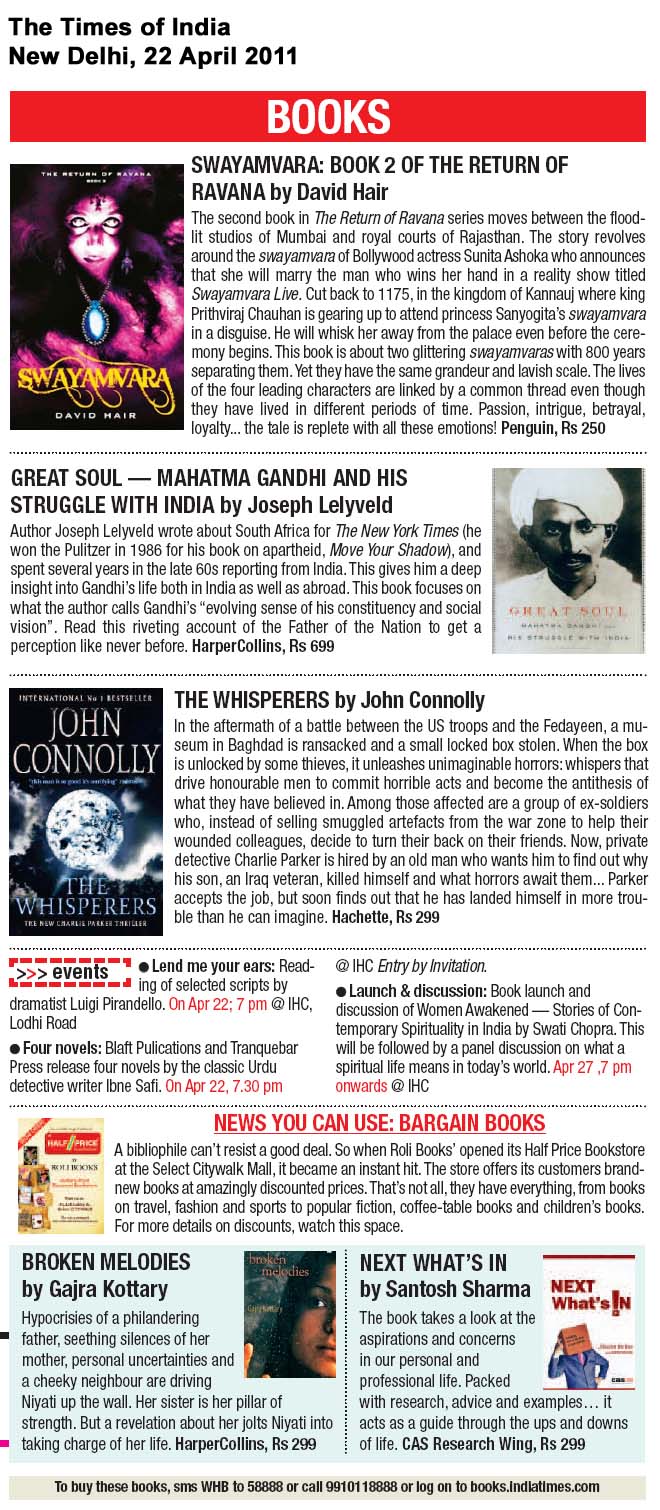

Niyati noticed that today Paaji was looking more preoccupied than he usually did when he ate his dinner. Soon he got up and retired as usual to his room. Mummy, Nisha and Niyati ate quietly. Mummy was still in her saree. Her lipstick had waned to a trace after the day’s toil and her hair was still tied in a bun, though the neatness had been disturbed.

Paaji emerged from the bedroom looking irritated.

‘Why hasn’t the cooler tank been filled?’

Mummy answered without looking up.

‘The water supply went off earlier than usual this morning and I had been busy cooking for the day. I couldn’t fill the tank.’

Paaji sighed in resignation.

‘Nisha, help your Mummy to fill the tank after you have eaten.’ After a pause he added, ‘Sumiran, if you would be at home instead of office, these things would not be neglected.’

Mummy looked at him: ‘It’s not as if I enjoy going to that horrible government office and slogging away at dusty files all day with just my typewriter for company. But this is the only way I can provide public school education and a good future for my girls,’ she said.

‘Huh, I get it. A good future that I have obviously not been able to provide! Say it Sumiran, say what’s in your heart. Say that you regret leaving the luxuries of your wealthy parents’ home to marry a poor but self-respecting artiste like me. Say it!’ he spoke in a voice quivering with hurt.

But Mummy had not said exactly that. She said with hurt in her voice, ‘I am not complaining…I chose to marry you and I stand by my choice…I don’t regret anything, except for the fact that you have changed so much since the marriage. You only think of yourself and no one else, since a long time now.’

Paaji’s eyes were now flashing. ‘No Sumiran, no. It’s you who never thinks about me, Sumiran. Once upon a time you loved my music. You loved everything about me, even my poverty. Not now, not since I can remember.’

‘Now, I love our children. Is that any less?’ Mummy asked, self-righteously.

Paaji heaved a loud sigh and went into his room looking exasperated. Niyati felt her throat tighten. She fought her tears with silent valiance.

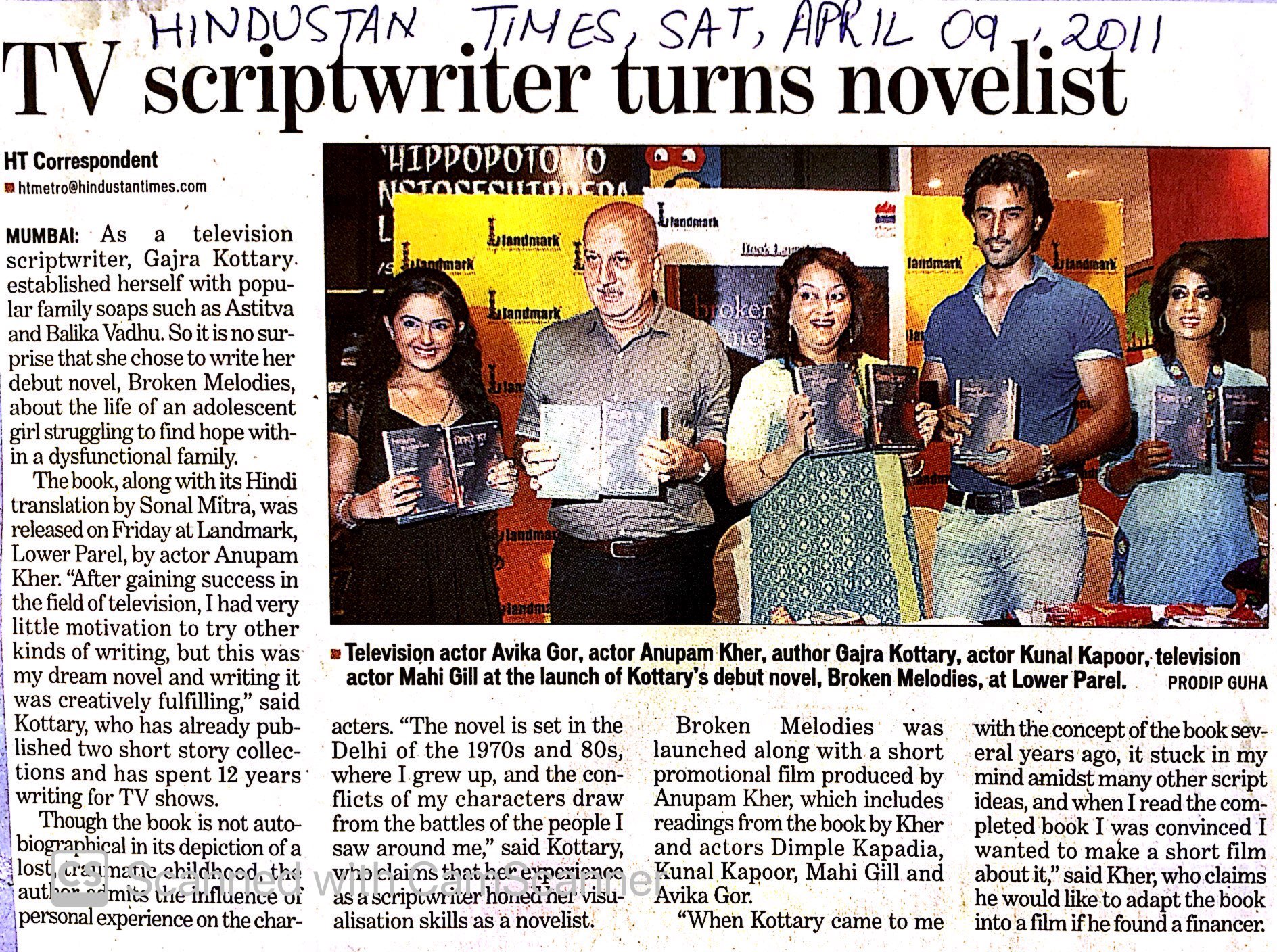

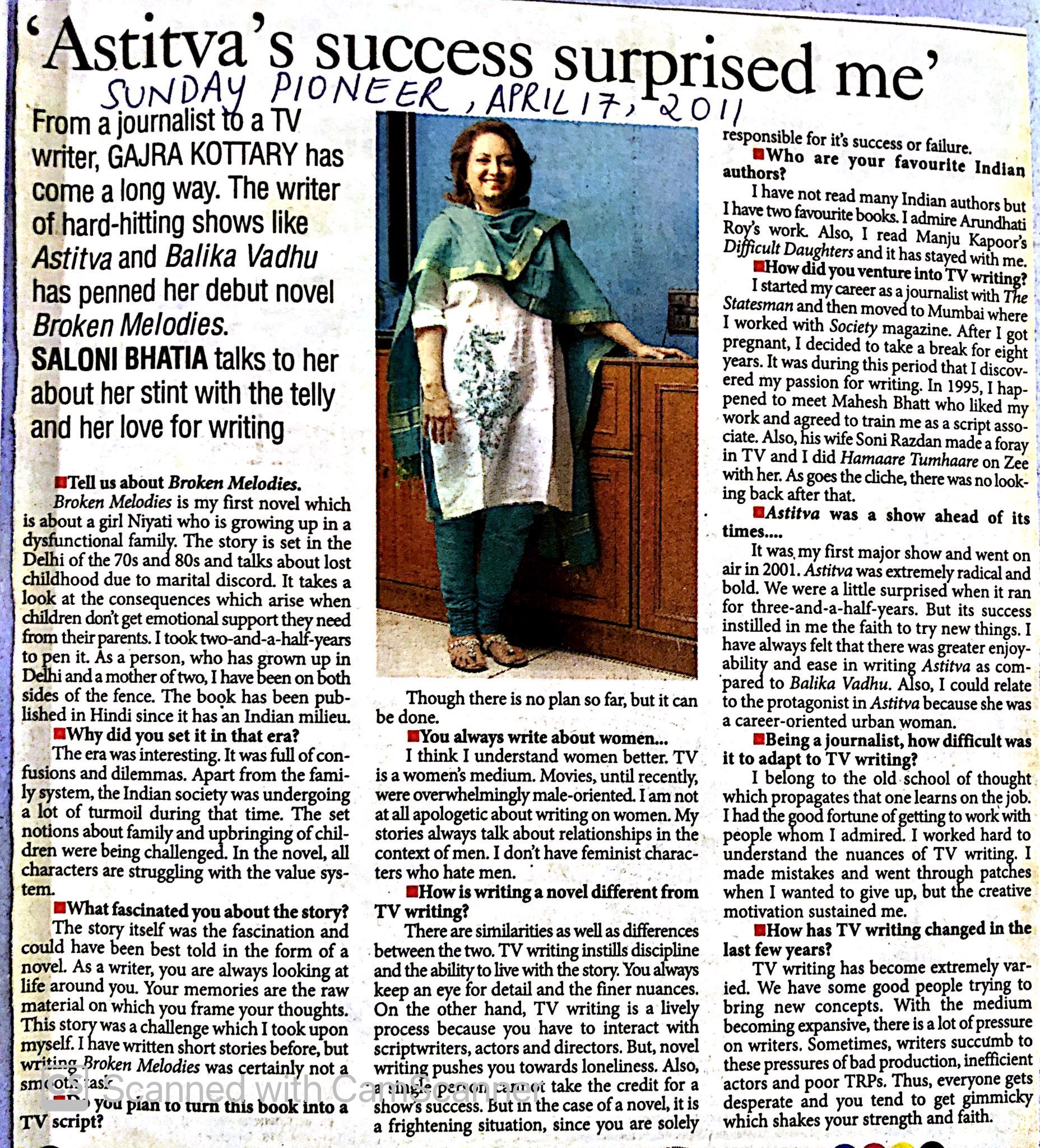

It was hard to imagine that the story that Mummy had so often told her about Paaji and herself had really been true, she thought as she stared bleary-eyed at her game. Mummy – better known as Sumiran then – had fallen in love with Paaji’s voice on the radio, and had secretly gone to meet him at the All India Radio in Delhi. She started learning music from him and was soon accompanying him on the tanpura as he sang, much to the shock of her mercantile family.

This would not have been possible if she and her family had at that time not been living for several months at a refugee camp in Delhi after the Partition in 1947. For if she had been in her mansion in Multan in normal times, her family would have married her off into another wealthy family of the city soon after college. Her studies would have then been viewed as the indulgence of a fond father to introduce modernity in his daughter’s life. They would not have been even vaguely considered as the means to employment that would be compensation for her future family in lieu of dowry, that was now impossible for them to offer.

Perhaps that was why Sumiran’s family gave in easily when she announced her decision to marry Shankar Chand, although they understood very little about art and artistes.

Each time Mummy narrated the story of her romance and marriage to Paaji to her daughters, she would initially giggle a little as they stared at her in disbelief. At such times, it was as though the excitement of her romance and falling in love were a separate entity, completely divorced from the reality of her present life with Paaji. Whenever she reached here and now, she would suddenly stop and then start talking of something else, even as her daughters, especially Nisha, hungered for more.

Sometimes she would tell the story of her great escape from Multan to Delhi as a teenager during Partition. Of how she was bundled from place to place in a huge gunny sack of rice, just about managing to breathe through its coarse jute fibre, until they were safely within closed confines again. That’s why Mummy always hated eating rice; she felt that she had had enough of its flavour to last her a lifetime.

Niyati looked at her puzzle again and decided that she would just not be able to finish solving it today. She moved away to join Didi in their bedroom.

After the cooler tank was filled, Mummy retired to the master bedroom where Paaji was resting. As Niyati climbed the stairs with Nisha, she heard the bathroom door open and shut, and then she heard water flowing into the bucket from the tap.

Mummy was taking her night-time bath.

Upstairs, Didi slipped into her nightie. Niyati slipped into hers. They both lay down on the double bed and turned on the night lamp.

‘Didi, what do you do in college?’ Niyati loved this bedtime tete-a-tete with Didi.

‘I study English literature and make new friends,’ was the matter-of-fact reply, as Nisha got up and opened her almirah.

‘Didi, are you going to get married after college?’

Nisha spun around and laughed lightly.

‘No, silly girl! Why do you ask?’

‘Pinky said today that she will get married after college.’

‘Oh! That Pinky! Let us not talk about her.’ Nisha was dismis-sive. ‘She is such a behenji!’ she added. ‘Hansraj College girls just have to get married as soon as they can; what else can they think of doing? But Miranda girls – we know how to find a life! Who cares about marriage?’ Nisha said with panache.

‘Why? Is marriage something bad?’ asked Niyati.

Nisha suddenly became grim. She looked at Niyati and a painful discomfort flashed across her face.

‘Let it go… Come on, time to sleep, Gudiya,’ Nisha said, as she tucked her into bed.

Nisha then went to her almirah and retrieved her secret pocket transistor. Coming back to bed she switched it on, but this time, the volume was controlled carefully by her. In the dim light of the night lamp, Niyati could see her hugging it close to her ear, fingers tapping against the head of the bed. Niyati dozed in and out of an overpowering slumber, each time opening her eyes to see Didi lost in the songs.

The transistor was switched off at eleven, when the station called it a night. The sounds in the house had settled by now, too. The only sound heard was that of the whirring coolers in the rooms. But even through her slumber Niyati was scared that the awakening would come soon and without a warning. And as usual, she had not prepared herself for it.

Sure enough, it soon did. Sitting up in bed, she wondered, like she did every other night, about what really woke her up like this. Was it because of the too long an afternoon slumber? Or was it something else? Niyati’s throat felt parched and dry.

‘Didi…. I need some cold water,’ she muttered.

It was no use, for by now, Nisha was drowned in sleep. Niyati wore her slippers and slowly made her way down the stairs.

As she descended the flight of stairs and walked towards the kitchen, she passed by Paaji and Mummy’s bedroom. The door was shut tightly. Niyati stood outside the door, wondering whether to call out to Mummy for water or go all the way to the kitchen on her own.

She heard their voices from inside the room. They were subtle and submerged in the drone of the cooler inside the room, but fed her curiosity enough to make her strain to hear more. Paaji and Mummy were talking intermittently. Then there was silence, and then came Mummy’s stifled sobs. Then there were murmurings, more in Paaji’s voice. Finally, the words began to fade out.

The spate of sounds confounded her weary mind. Fear surged in her and suddenly, she was aware of her thirst again. Niyati hurried to the kitchen and helped herself to a glass of water from the refrigerator.

When she returned towards the stairs, she stopped again, outside their door. There was silence all around. She turned to leave and heard moans emanating from inside – stifled exclamations of laughter, then a gasp, and then a cry…? She couldn’t make out anything clearly. She felt a confused, paralyzing fear. Then, she walked away, as fast as the shadows of darkness would allow her to.

Back in bed, she lay next to Didi, turning the sounds she had just heard over in her mind. The sounds in her head were dodging each other – sob, moan, moan, sob, talk, silence, giggle, cry. The see-saw motion of thoughts assaulted her fatigue and killed the remnants of wakefulness. Before she knew it, Niyati had dozed off again.

Morning brought with it an uneasy silence. Paaji was in his room, singing Raga Bhairavi. One of his students was taking an early morning lesson and the tanpura sang sadly along with Paaji. Niyati sat on the khadi rug working at her puzzle, while waiting for Mummy to get her tiffin box ready. Eight more pieces to go. The last part was usually easy and always made her feel good about herself, but this time it just wasn’t so easy.

‘What are you struggling with so much since yesterday?’ asked Nisha. Mummy had sent the tiffin with her. ‘Take this and keep it in your bag.’

Niyati mechanically did what she was told, but mumbled with frustration.

‘I can’t finish this, Didi.’

Nisha smiled indulgently.

‘Let it be, Gudiya…these pieces are so faded and old, you’ll probably never understand where to put what. Could be that some of them are missing too!’

By now Niyati had picked up her heavy school bag and slung her bottle around her neck. She ran out as soon as she heard the school bus trundling towards her gate.

Remembering what had happened the previous day, today Niyati locked the door of the gate by moving the horizontal bar into its loop. Chandan was highly unwelcome in these five minutes of personal space that she prized so much. Or at least she would be warned about his coming, instead of him just appearing from nowhere like he usually did.

Her customary scan of the house didn’t reveal anything different. But a strange acrid smell hit her nostrils the minute she stepped inside that afternoon.

‘Niyateee…? Niyateee!’ Nimmi aunty was yelling from the other side of the wall.

Niyati opened the window a little and called out, ‘I’m coming, aunty! I’m coming in a minute.’

Niyati felt the need to pee. She hated to pee in Nimmi aunty’s toilet, because every time she came back from there, Chandan gave her a weird look, which made her cheeks turn red and hot with shame. Niyati hurried to the toilet attached to Paaji’s big room and pushed open the door. The same acrid smell blew right into her face and startled her.

On the mosaic floor of the bathroom was Paaji’s lungi, or what was left of it; his favourite blue-and-mustard checked one. The singed cloth had huge, gaping holes, and was smelling strongly of kerosene.

Her nose smarting with the smell, Niyati used the toilet, eyes constantly on the burnt lungi. When she had finished, she walked carefully around the cloth before she reached the door and ran out quickly as if scared that the cloth might decide to get a life of its own and follow her out. She didn’t want to lie down on the divan even for a moment today.

The hot May sun was unable to loosen the smell, which had by now seeped right into her. As she reached Nimmi aunty’s door, Niyati stopped and panted for breath. Beads of perspiration were rolling down her small forehead as she rang the doorbell.

Nimmi aunty quickly opened the door and pulled her inside. It was so cool in her house. The welcome blast of cold made her forget all her worries for a few seconds. Until she saw that horribly familiar, nauseating look of concern on Nimmi aunty’s face again. There she stood, kindness oozing from every bit of her jiggling body.

‘Aa gayi, puttar? she stated the obvious and then proceeded. ‘Come, let’s eat…Chandan, you also come.’

It was then that Niyati saw him moving out of a dark corner. A faint chill ran down her spine. How she hated the way he always popped up from places!

Niyati began nibbling at her food. She ate all that was there, but the food was a distant experience right now. The only thing she could think of was the burnt lungi.

Nimmi aunty’s very first statement pierced through her stoic silence.

‘Niyati, today you will stay here at night also,’ said Nimmi aunty, heaping baingan ka bhurta onto her son’s plate, then turning to Niyati, asking ever so kindly, ‘Want some?’

Niyati blinked and shook her head. Chandan smiled his sarcastic smile.

‘Your Paaji is not well, my child. Mummy has taken him to hospital.’

‘Why aunty?’

‘Nothing to worry about! Paaji will be back home in one or two days.’

Perhaps this weird interface was not really happening, thought Niyati. Maybe it was like one of those nightmares she often had.

She gobbled her lunch at record speed that day, as if trying to comfort her incoherence with food. Later Pinky arrived and joined them at the table. Niyati went and sat on the sofa, waiting for the princess of the Chopra household to finish lunch and take charge of her as she often did. But Pinky’s quick words soon became a distant hum to Niyati as she slipped into a tired nap on the sofa. Before she fell asleep, she thought of her unfinished puzzle at home.

Dusk brought with it that familiar sense of despair again. In sheer contrast to her thoughts, as Niyati sat in the Chopra house, were the various noises of robust living emanating from the three members present in the house, and most of all, of course, from Nimmi aunty and Pinky.

‘Mummy! Let me buy a new pink salwar-kameez please.’

‘How many pinks you need, Pinkiye? You already have two pinks. Isn’t it so, Niyati?’ Nimmi aunty smiled at Niyati.

‘Yes, aunty-ji.’

‘But Mummy, pink suits me. Tell me Niyati, doesn’t it?’

‘Yes, Pinky didi,’ replied Niyati, almost grateful to Pinky for this mundane discussion.

‘Cho chweet! Look, Mummy, Niyati also says so!’

Nimmi aunty laughed and her round, protruding stomach shook dutifully like jelly.

‘Hai main sadke jaanva, Pinkiye,’ Nimmi aunty went all mushy over her daughter. Turning to Niyati she added importantly, ‘You know, Niyati, when my Pinky was born, she was absolutely pink. Doctor said, your daughter is in the pink of health! We decided to call her Pinky since then!’ And she laughed even more, her ruddy cheeks going ruddier at this happy reliving of the Chopra family history.

Pinky giggled. Chandan smiled forcibly, but why exactly, Niyati didn’t understand.

Niyati, who hadn’t changed from her uniform till now, took the bag of clothes that Mummy had left for her and changed into her frock in the bedroom. A little later, she was offered a glass of milk with Bournvita. She finished it to the last sip, for fear of Nimmi aunty lecturing her yet again on how she mustn’t waste the beverage that could make her tall and strong, just like Pinky, of course.

Niyati ambled up to the main door after a while and looked out in the direction of her house. The lights had not come on and Niyati realized that what Nimmi aunty had told her about Paaji was for real. She remembered Nimmi aunty saying that Didi was at the hospital, too.

She made her way back into the living room where Chandan accosted her suddenly. ‘Your daddy is in hospital. Don’t you know why?’

Niyati stared at him wide-eyed, afraid to ask and even more afraid to hear what he would have to say.

‘But then, how would you know you dummy!’ he laughed, completely enjoying the suspense he had built up for her.

Somehow, though she was very curious, Niyati didn’t want to hear it from Chandan. She ran fast and far away from him, up the stairs, and barged straight into the sanctuary of Pinky’s room.

Pinky had laid out two sets of salwar-kurta on her bed and was comparing them seriously. She looked up at Niyati, who had tears in her eyes.

‘What happened, Niyati?’ she asked, her attention veering back to the clothes.

By now characteristically, Chandan had come up from behind.

‘What can happen with her…’ he began.

‘Chup kar, CC! Don’t disturb, let me concentrate. I have to decide which suit to wear to Pammi’s party.’

Chandan sniggered and went away defeated. Niyati felt safe and her tears had retreated by now.

When Prakash uncle came home at eight o’clock, it was still hot outside. A short, plump man, he parked his Bajaj Chetak outside the stairs and entered the house, perspiring. Prakash uncle was the proud owner of this scooter as well as a proudly maintained Fiat that he took out only on family outings, usually on Sundays, when it often had to be pushed by the entire family to get going. Nimmi aunty had proudly stitched lace curtains for all the windows of the car, which were tied in the middle with satin ribbons, and Prakash uncle had a magnificent little fan on the dashboard, all to himself, when he drove the family places. He was the complete family man and provider and looked as though he had been naturally born into the role.

He was balding right in the middle of his head and had clumps of hair scattered on his pate. It made him look very strange – so different from her graceful Paaji. Prakash uncle’s Karol Bagh leather sandals were dusty but rough and tough. He slumped onto his Jail Road sofa and wiped his forehead with his sweat-streaked handkerchief.

Despite this never-changing daily scenario of life, it was a wonder that Nimmi aunty always seemed thrilled to see him. She rushed inside to get a glass of cold water proudly from her Kelvinator fridge. She sat beside him as he drank noisily from the glass and said ‘Aahh!’ in naked pronouncement of relief.

‘I got very tired today. Many, many customers I got today at the shop,’ he said in his thin voice as Nimmi aunty fanned him with a hand fan. Her eyes shone with pride as she stared at the family picture hung on the wall above the sofa that had been framed recently upon her insistence. It had been so difficult, finally getting a picture this perfect, from the reel of thirty-six that the photographer had exposed; reels were expensive these days.

Hence it meant that the photographer spent half an hour preparing, ‘setting’ and ‘posing’ for each (black-and-white) picture. That’s why, except for the supercool and perfectly posing Pinky, everyone else in this picture seemed to be standing in attention, holding their breath. But Nimmi aunty was extremely proud of this picture nevertheless.

Prakash uncle had a small shop of electrical goods in Laxmi Nagar. He was very proud of his shop, as much as he was of his family, especially his daughter and wife. The only issue he had was with his son. It was because Chandan often disdainfully told him that when he grew up he was not going to join his business – never ever. When Prakash saw Niyati at his place at that hour, he was surprised.

‘Niyati beta! You didn’t go home yet, puttar? Your Paaji must be waiting for you!’

Nimmi aunty was all charged up.

‘Niyati’s Paaji is in hospital. That’s why the poor thing will be staying with us tonight, ji!’ she explained with exaggerated pity.

‘Achcha? But…’ Prakash uncle wanted to know more, but a certain look from Nimmi aunty and her switching the topic to dinner stopped him from asking anything further. The silent

exchange of glances between them gore Niyati like a dagger.

Thankfully, Prakash uncle soon looked importantly at his HMT watch and realized that it was time for him to watch the news on TV. He proudly walked towards and switched on his recently acquired Weston TV, thoughtfully fixed with a tricoloured anti-glare screen, attached with two side clips, and duly protected by a lovingly crocheted cover made by his wife.

The TV was the most prized possession of the Chopra household these days. Especially on Wednesday nights at 8:30 p.m., when Chitrahaar – the half-hour-long programme of Hindi film songs – was aired and of course the Sunday evening movies, too. At these times, it was normal to expect the neighbours – both familiar and sundry – to invite themselves over to watch TV; it mattered little if they knew the owners or not. Of course, Niyati and Nisha had been banned from going there to watch TV like the other neighbours, unless it was a really special occasion.

The only time that the Chopras were spared these biweekly intrusions was on the death of any political leader because of the period of mourning they would announce on TV. And during those days, Doordarshan only aired classical music programmes and even Salma Sultan suppressed her smiles, so viewership dwindled drastically.

Over these last few weeks, Prakash uncle had learned to be fairly tolerant to the visits of the neighbours as encouraged by his ever sociable wife only because it was not something that he needed to endure every day. Thankfully, the news did not interest the neighbours as much as him.

Nimmi aunty, taking the cue from Prakash uncle, now went in to do her last-minute touch-ups for dinner, and whirred her mixer proudly to make cold lassi as an accompaniment with the meal, as Niyati basked in the relief of temporarily being ignored.

Dinner was ever so delicious, as all food here always was – the comforting and welcome combination of aloo-gobi and mutter-paneer.

Post all the fuss at dinner, Pinky was instructed to take Niyati up to her room. Chandan was asked to adjust on the huge Jail Road sofa for the night. He looked at Niyati contemptuously as he accepted the change reluctantly, but Niyati cleverly avoided his long stare.

Pinky’s rattling continued for half an hour after the lights went out. Strangely, she was going on and on to Niyati about how she and her group of friends in college used to jam to all the songs of Abba and Boney M as she proceeded to hum ‘Mama Mia’ in a very very desi way. And then she blissfully drifted into sleep. Niyati remained awake for a while. She thought she heard the familiar strains of Nimmi aunty’s favourite programme, Hawa Mahal, playing on the radio from within her bedroom downstairs. Sleep was the best thing God invented, she thought for the nth time, before she thankfully gave in. Before sleeping however, Niyati prayed fervently that the mysterious thirst that visited her every night would give it a miss today.

But soon she got up with a start. She had been uncomfortable asking Nimmi aunty for a bottle of water for the night before she retired, and now the discomfort in her throat was increasing. For what seemed an eternity, Niyati stayed put, not knowing what to do.

Finally, when she couldn’t manage it any longer, she rose from bed and tiptoed down the stairs. As she waited at the foot of the stairs, wondering whether she should wake up Nimmi aunty or find a glass and take a bottle from the fridge herself, she heard voices murmuring.

A faint light streamed out of Nimmi aunty’s bedroom door, a little away from the kitchen. Niyati was relieved. Maybe Nimmi aunty was awake. Gathering her wits, she walked noiselessly towards the room. As she was about to knock at the door, the word ‘Sumiran’ struck her ears.

‘Arre, those who saw it said that smoke was coming out of the bathroom window!’ Nimmi aunty’s voice was a loud whisper. ‘Shankar Chand and Sumiran had had a fight half an hour before that. Shankar Chand, they say, was very angry, and in his anger, he locked himself inside the bathroom and tried to burn himself !’

‘Really? Such a big fight…for what?’ Prakash uncle’s thin voice was sharper and much clearer than hers. Nimmi aunty’s voice giggled. ‘Pata nahin, ji. Mrs Chadha was saying that Shankar Chand had a break-up with some student of his. He was having an affair with her. Something like that…. God knows what the truth is.’ She paused with a long sigh. ‘Chhodo na, ji, how does it concern us…. Thank God, we don’t have such problems in our family.’

‘Hmm,’ grunted Prakash uncle.

‘I hope you won’t do anything like this with me, na? I know that you will always remain mine only and not do these affairs?’ Nimmi aunty was telling him coyly. Niyati could hear the bed creaking now.

‘Should I have one?’ Prakash uncle said teasingly and the bed creaked some more. Niyati felt the same uncomfortable feeling flushing through her, the kind she felt when she heard noises from her parents’ bedroom.

‘Chalo hato!’ protested Nimmi aunty and her giggle and Uncle’s thin funny laughter mingled with the creaking and produced an even deeper discomfort in Niyati. ‘No darling! You are for me only,’ Nimmi aunty was saying. ‘You are so good darlingji….’ she moaned as the bed creaked more.

‘Mmmm! Haye re, I think you will eat me up only today!’ she said as she giggled in between.

Prakash uncle grunted back, ‘You are too tasty, my Nimmo! I don’t need anybody else like that Shankar Chand!’ He heaved a sigh of relief as he continued. ‘All these are artiston ke nakhre and chonchle baba. We regular people are better off than them, at least we have some values!’

Nimmi aunty was giggling uncontrollably now, and Prakash uncle laughed at her sounds. Their sounds pierced through Niyati’s heart like a knife. Actually like the sua – she had gently tried piercing it against her skin, to see what it felt like.

The sua so often came in her dreams. It was a sharp instrument that hung in the kitchen and always stared at her threateningly, carrying in its tip many a dramatic tale of Shankar Chand Nivas. By now, Niyati’s heart was thumping wildly inside her small frame, almost as if it was going to jump out any minute.

She turned to go and bumped straight into Chandan. Startled, Niyati was about to scream but Chandan swiftly covered her mouth with his palm and pushed her towards the kitchen.

‘You don’t utter a sound now, you nosy bee. Shameless wretch! Listening outside others’ bedrooms!’

Niyati froze in fear.

Chandan slowly removed his hand from over her mouth.

Tears running down her cheeks, Niyati fled up the stairs. Chandan stood there watching after her like a hawk.